Day 4 (This is part four of a multi-part series. To start at part one, click here: https://authorrickfuller.com/2024/03/24/trekking-the-largest-cave-in-the-world-hang-son-doong-vietnam/)

Waking up on the final day of a long trek brings a bittersweet feeling. The tour has been lengthy enough that you’re ready for it to conclude, yet you know you’ll miss it once it’s over. You’ll look back on this moment, wishing you could return, spending more time soaking in the sights, smells, and the magnificence of this transient experience. The outside world awaits with its ebbs and flows, the hectic, frenetic pace of normal life that we’ve nearly forgotten while immersed in this incredible cave with no external contact. We understand that we must rejoin that world, ready or not, and so this ultimate wakeup carries a sense of anticipation tinged with a slight foreboding, blending into that undefinable bittersweet sensation.

I’m awake this morning at 4am, the darkness and peaceful quiet of the still camp telling me the approximate hour before my watch confirms it. I know that this is going to be a taxing day full of grueling ascents and descents, and sleep is going to be paramount toward getting the most enjoyment out of the effort, and yet the anticipation of the day forces sleep to elude me. I lay restlessly until 7am and then finally exit the tent to a dot of blue sky in the doline far above. The normal routine of coffee and organization of our gear follows before the call to breakfast is given. Our fare this morning is French toast, called “egg toast” by our team, which allows me to pretend that I’m not eating French toast after all and thus, do not need any maple syrup. Accompaniments include fried rice with and without meat, and lots of fried and steamed vegetables, and there is, as usual, too much for us to even come close to finishing.

After breakfast, we don the five-point safety harnesses which the safety assistants secure under the watchful eye of Hieu who double-checks their work when they finish. Today we’ll be exiting the cave via a strenuous and long climb, and harnessing us here in the light from the doline is much easier and safer than trying to do it in the darkness later, despite the large distance we still have to traverse before they’re actually needed.

We leave camp at 9:15, trekking away from the light and into the darkness once more, headlamps atop caving helmets illuminating the gloom, carabiners clanking rhythmically to our steps. Even our group’s safety assistants are quiet this morning, a pensive and almost maudlin countenance on every face that flashes though my light. I have no doubt that for them, this is always rather difficult. They’ve gotten close to many of us, chatting and sharing life stories, and they know that they’ll likely never see us again after today. And then, after a few days of resting at home, they’ll meet a new group of ten and start over, in a repeating cycle of almost getting to know someone before they leave your life forever. While we’ll remember their faces for a long time, both in the memory of an incredible experience and in photo, the memory of our faces will quickly ablate to them, fading away to be forgotten in the blur of client group after client group.

Our path today is flat and easy, well-marked with ribbons that keep us from marring the ancient formations we pass. And these formations are absolutely magnificent. Massive stalagmites once again greet us as we wind around them, trekking over voluminous calcite flows that often seem to have sprung from the walls. We stop at a stalactite formation with a very unique shape called “The Dog’s Bollocks” that comes to a point maybe four feet off the ground, a perfect spot for posed photos, and all but one of the group participates with joy, the lone holdout a curmudgeonly old naysayer dashingly youthful adventurer who looks on with impatience and annoyance contentment and delight.

*Confession: It was me. I was the lone holdout.

While the photo shoot ensues, I take the time to study the incredible formations caused by millennia of dripping water. My writing skills are not up to the task of describing these ridiculous etchings which seem to somehow have both uniformity and chaos, a random walk in a roomful of mirrors perhaps. I’ll let the picture speak where my skills lack.

After an easy walk in the magnificent forest of cave formations, we traverse massive underground sand dunes, safety assistants spreading out once more with powerful lights to display the full grandeur of the massive cave that houses these unique dunes. We then pass an area that is packed with cave pearls trapped in intricately weaving gour dams formed by shifting waters and swirling minerals. These alone would be fascinating artifacts were it not for the massive sensory overload of four days of this cave. There are only so many ways to say, “magnificent, huge, amazing, spectacular, incredible, and mind-blowing,” and my brain is spilling over with the sights I’ve seen. I can’t take any more magnificence, and this more than anything else tells me that it is indeed time to get back to the real world.

We move on, crossing a region of sand dunes and then through a massive cavern which the crew lights up for us again. After an appropriate amount of marveling, we trek across the cavern and drop down by means of a rope handhold and soon arrive at the lake zone. This is a wide spot in a massive cavern, and in some seasons, this is a tremendous (magnificent, huge, amazing, spectacular, incredible, mind-blowing) lake that is held at bay by the natural dam known as the Great Wall of Vietnam. More on that in a minute.

This lake is often deep enough so as to require passage by boat. Today, it is a huge field of mud, and these boats are tied up in front of us, resting on the mud as if waiting for the tide. Because there is no lake at the moment, our destiny is a muddy trek away instead, and we wind down into a very narrow channel approximately six to twelve inches wide, with steep, muddy slopes spanning up and away ten to fifteen feet high on both sides. The channel contains three to four inches of mud with about a foot of water on top, and we splash through that channel in single file, using our hands against the muddy walls of the bank to steady our approach. The mud sucks at our feet with every step, and the serpentine path winds its way forward, unseen deeper spots forcing a slow passage lest we trip or stumble and end up covered in the viscous goo that now surrounds us.

One of the safety assistants leads the way, and Jeremy and I follow, quickly outpacing the rest of the group, the only sign of their passage the occasional reflection of light from their headlamps. After thirty minutes of walking the thin line like a drunk performing a sobriety test, with, much like that drunk, many stumbles and lots of arm waving for balance, we finally arrive at the Great Wall of Vietnam.

This wall was first encountered by the British caving team during their exploratory surveying. A massive vertical wall that disappears into the darkness above, they originally had no way to scale it. By turning off their lights, they could see a faint glimmer of daylight far above, and they had no way of knowing if they were seeing the exit from the cave or yet another doline. Returning with climbing equipment, they now had to figure out how to drive anchor bolts into calcite, a task that does not inspire confidence when one is ascending a great height. The story of these cave experts solving the puzzle of conquering the Great Wall is a good one, but beyond the scope of this blog, however, one line tells the tale better than any other:

“8 meters up seems a long, long way when you’re 5 kilometers into a cave, 10,000 kilometers away from home, hanging from a bolt installed in something with the consistency of wet putty.” – Sweeny, member of the BCRA, who first conquered the Great Wall of Vietnam.

Because the ascension of the wall remained difficult and dangerous for many years, until 2017 tours ended here, clients forced to retrace their steps all the way back through the cave, exiting the same way they came in, a longer and more exhausting tour undoubtedly. Today, the wall has been solved via a massive (amazing, spectacular, incredible, huge…) ladder.

This ladder, made of steel and reinforced with supports that have been drilled through the wall and massive struts, rises 120 feet in height, its top disappearing into the darkness, beyond the reach of our headlamps. Jeremy and I stand on a narrow ledge below the ladder, the river roaring away just barely visible below us, a potential fall disastrous as any slip would lead us to undoubtedly be swept away, into the river and underground, and the waiting here seems rather pointlessly dangerous as we shuffle on tired feet trying not to bump each other off the ledge and into oblivion.

There is a pipe that is tapped into the river, and water pours from it into a bucket with scrub brushes. The safety assistant who led us here scrubs himself clean of mud before calling us over one-by-one to scrub the mud from our boots and legs. Any trekking of mud onto the ladder or onto the wall that awaits somewhere above the ladder would make it slippery and dangerous for those following, and the crew takes their time removing all vestiges of mud with scrub brushes dipped into the bucket.

When we’re clean, we stand on a curved and sloping rock just inches away from that potential tumble into the rushing river, and I hope that I haven’t done anything to offend Jeremy over the last three days as we await the arrival of the rest of the group. Luckily the surface on which we stand has the consistency of sandpaper, and traction is great, though the looming chance of death behind us serves to keep our apprehension elevated.

Tha arrives along with the other safety assistants, and they clean themselves off before the assistants scoot up the ladder to secure their positions on the wall where they’ll be helping guide us from section to section of this long climb back to the surface. The waiting game drags on as orders are shouted in Vietnamese up and down the height of the wall, and the anticipation of this exercise keeps all of us buried in our own thoughts. Finally, Tha signals that we’re ready to begin.

We pair off in groups of two, and Tracy and I are elected to be the first to climb. Tracy motions me forward and I step first onto a horizontal ladder that spans ten feet over the raging river. Iron bars rammed into the muddy bank provide handholds and I quickly cross the span and then stand at the bottom of the massive ladder. I can’t help but marvel at the herculean effort required to move a gargantuan contraption like this first into the cave, and then into position at the base of the Great Wall. 120 feet in height and bracketed into the wall with thick steel supports, the story of how it was placed is one I want to hear. However, there is no time.

Tha checks my boots once more and finds them not clean enough, so he takes another scrub brush to them to eliminate the remaining mud. He then clips my center ring into a rope and shouts up into the darkness far above. Slack is pulled up and my harness straps are pulled taut. Tha and I nod at each other and he gives me the green light to begin the climb.

I move quickly, admiring the views as I ascend into the darkness, the vertical wall getting closer as I near the top. I’m breathing hard when I reach the top, and beads of sweat have begun to coat my body in the thick humidity. There’s a narrow ledge here where the pitch of the Great Wall turns from 90 degrees to about 60 degrees, and I step off the ladder and onto that ledge. The safety assistant waiting there clips my two free carabiners onto a safety rope that is anchored to the wall, and then clips a new support rope to my center ring. He asks me if I want to rest, but I am amped up and I reply, “No, let’s go.” He calls up the slope far above and the slack in the new rope is pulled up, and I begin to climb again, leaning back with the rope between my legs and my boots grabbing purchase on the sandpaper-like slope of the wall. I again move quickly, climbing as fast and hard as I can in some bizarre race to outclimb the safety rope. I have no idea why I feel that I need to outclimb the safety rope or why I can’t just enjoy the climb, but the purely fabricated competition drives me to the top. By the time I reach the next ledge, perhaps forty meters above the top of the ladder, I’m drenched in sweat, panting for breath, my arms weakened through the effort. Here, I do take a quick break, until I hear the shouts from below and realize that Tracy has begun her ascent of the ladder. Panic over potentially being a cog in the operation rears up, and my race against my own brain begins anew. Still panting like Seattle Slough on the 10th furlong, I nevertheless grab the new line and step onto a 45-degree slope, racing my way up this last section until I triumphantly arrive at the very top of the wall.

I’ve won the race. Against myself. Yippee.

I’m drenched in sweat but I couldn’t be happier.

The Great Wall of Vietnam is a truly amazing feature of Hang Son Doong, and by my estimation, more people have ascended to the top of Mount Everest than have climbed this wall, which means very little except in my head, but which is still a pretty cool stat nonetheless. After Tracy reaches the top, we are escorted off to the side of the cave where a large shelf juts out, providing a nice viewing area of the top section of the climb. From there, we cheer on the rest of the group, taking pictures and videos and shouting encouragement. After the last climber, the rest of the safety team climbs up, moving far quicker than any of us, including myself, while carrying their big, heavy packs. They are truly impressive.

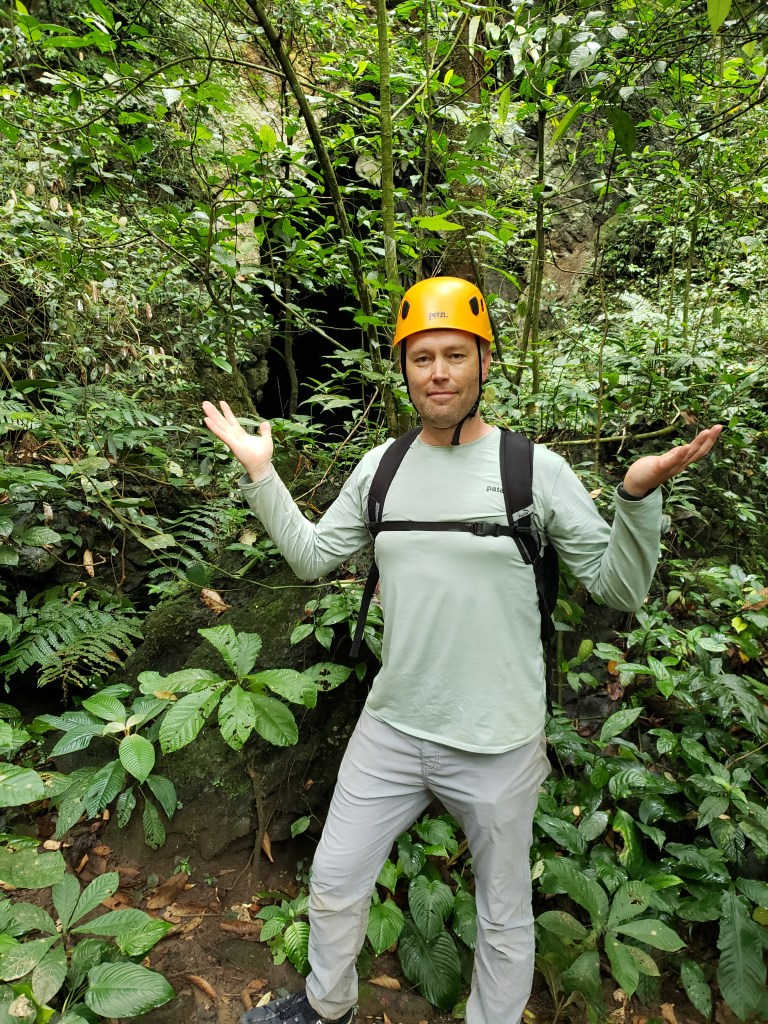

When all have safely navigated the climb, we have lunch, the light from the cave exit visible in the distance. The cave trek is ending, and we are all flying high from the much-anticipated climb of the Great Wall. Lunch finished, we move quickly the remaining distance and then climb a steep, rock-strewn slope toward the light of day. After three days of immersion inside the largest cave on the planet, we step out of the cave and back into the jungle.

Only a few steps from the exit, the dark maw of the cave is swallowed by the jungle, all traces disappearing, and once again, this really reinforces the previously inconceivable idea that the cave had remained hidden for so long. Here, in the middle of a dense jungle, very high on the top of one of thousands of limestone monoliths, far from any civilization, this narrow opening, covered by the thick vegetation, could very conceivably have never been found.

Although this feels like the end of the trip, it is anything but. In fact, the hard part is yet to come, a nice little secret not talked about by most. Unlike most, I spread truth, and I’m therefore going to be the first to tell you, that the descent from the cave exit is one of the toughest downclimbs I’ve ever done. We first pass a ranger who guards the cave from unauthorized visitors. I marvel at his camp which is perched very high on the mountain. Tha tells us that he will stay here for three to four days straight until he is relieved, and that this cave entrance is guarded 24/7. This job, sleeping in a tent in the deep jungle, far from civilization, out of cell phone range, all alone for three to four days, is one that I think would drive me completely crazy after more than a shift or two.

After passing the one flat spot on the jungle-covered mountain, we begin the descent. We’re told that our caving helmets are required for this descent, and though it annoys me to wear this thing in the heat of the day in the steamy jungle, I completely understand the necessity. The slope is rock-covered mud, with many spots that require holding onto a rope while navigating a slope of 70+ degrees. When we’re not trekking barely manageable slopes, we’re moving from knife edge to knife edge, wobblily stepping across chasms just waiting to break a leg. Tha tells me that he was seriously injured once on this descent when he gashed open his leg on one of the knife-edge rocks, and Hieu was so badly hurt in a fall here that he had to be carried out by the porter team. This descent is absolutely no joke, and we are all panting, aching, and covered in sweat by the time we finally reach the dry river bed that marks the bottom of the valley. Although it took only an hour to get here from the cave exit, it was by far the toughest hour of the entire trek, and we are exhausted.

We rest here for a bit, drinking water to rehydrate. I move up the river valley to relieve myself and find an entrance to yet another massive cave. Returning, I tell Tha about my discovery and ask if we can name it Hang Rick, but to my utter disappointment, he claims to already be aware of it, and in fact tells me that Oxalis provides a tour through it.

As I pick up my pack, I realize that Tha has filled the outside pockets with heavy river rocks, a rather funny joke that would have been better if he’d put them into the zippered pouches so I didn’t see them. I empty the pockets and we now climb out of the valley. It takes us 20 minutes of tough climbing on the well-trodden path before we pop out of the jungle and back onto the Ho Chi Minh trail. Jeremy, the old man of the group is the first to arrive, and when I pop out, he has already cracked open a beer which the crew has thoughtfully provided in an ice-packed cooler that is awaiting our arrival.

The porter team has beat us here (of course) and they lounge around in the shade, smiling and cheering for each of us as we pop up out of the jungle and onto the road. It’s 3:30pm and we are exhausted as we chug the beer and high-five all around. We truly feel that we’ve accomplished something incredible, and we’re excited and proud to have successfully and safely completed this incredible trek.

Epilogue:

The tour doesn’t officially end at the roadside, though it may feel that way. The price includes a stay that night in a beautiful bungalow at a place called Chay Lap Farmstay, where the ten of us gather for a last supper with our guide Tha Tran, and our safety specialist Hieu Ho. The dinner is wonderful, and afterwards we take another group picture and then Tha and Hieu hand out wooden medals to commemorate our trek.

On the nightstand in our bungalow room was an envelope where we could provide an optional tip to the 26 members of the Oxalis staff who catered to our every need for four days straight and ensured that we successfully turned this dream into reality. When we first booked this adventure a year previously (the tours fill up early, and a one-year advance booking is usually the minimum) we weren’t sure that it would end up being worth the $3,000 per person that they charge. It seemed like a lot of money at the time, especially in a country like Vietnam where a dollar goes a long way. After taking the trek, we were actually stunned that it was so cheap. Two full-time chefs who make every meal into a delectable feast. 17 porters who each carry monstrous packs through an arduous trek where us clients sometimes struggled with just day packs. 6 safety assistants who watched our every step to ensure we were safe and injury-free. A safety supervisor specially trained by the British Cave Research Association with top-notch modern cave trekking knowledge and skills. And lastly, an incredible guide who had the most magnetic, energy-filled personality you could ever want. And this doesn’t even begin to touch on the staff at Oxalis who put all this together from the time of booking to the time of our departure. The fee includes round-trip transportation from Dong Hoi, the two nights in the different bungalows that bracketed the actual trek, the roughly $750 per person fee that the Phong Nha-Ke Bang National Park charges for entry, and many more things. After tallying up what it should have cost, we were actually amazed that it was so cheap.

Upon embarking on this trip, we made sure to bring enough Vietnamese money to tip the staff at the end. We planned on a local-appropriate tip of somewhere in the 5-10% range, depending on the level of service and our satisfaction with the tour. After we finished, we realized that this was nowhere near enough. The level of service was absolutely exemplary, and the professionalism of every member of the staff was far and above any reasonable expectation. We were so appreciative that we felt compelled to show our gratitude in the only way a client truly can, and that was through a much more generous tip than we’d originally planned, and it still felt like it wasn’t enough. It’s incredibly rare to experience 6-days and 5 nights on a tour and not think there was at least some mishap or room for improvement, but Oxalis has managed to create an exemplary tour that addresses every conceivable issue with first-class service that I am dying to repeat sometime soon. My recommendation could not be more glowing.

The day after we exited the cave we had time to relax in the very nice bungalow and resort area. Every bit of our laundry, which had to be as disgusting as possible after most of our clothes sat wet for three or four days in a plastic bag, was professionally done at a total cost of somewhere around $10, and was waiting outside our room when we woke up. I took a complementary bicycle and explored the town with a 5-mile ride on an idyllic country road that winds through lush farmland with the cloud-enveloped and jungle-covered limestone mountains as the backdrop. At noon, the provided car service picked us up and we were driven to the train station in Dong Hoi where we weren’t taking a train, but were instead picked up by another car service I’d booked to take us back to Hue. The rest of our Vietnam trip, both before and after the cave tour was absolutely wonderful as well, though those details will have to wait for another time.

A trek through the incredible Hang Son Doong is an unforgettable, life-changing experience, and if you get the chance to take this journey, have no qualms or second guesses, just jump on it. You will not regret it!